Chill n’Fill

Episode: The Space Between Wanting and Taking

Written by: Emmitt Owens

(Index #01152026)

Authors Preliminary Notes: This episode is emotionally dense. This episode is a keystone—it defines what “healthy” looks like in this universe. Future episodes will bounce off it.

The thing about midnight is that it doesn’t lie. Whatever you bring through those doors at 12:47 AM is exactly what you are—no performance, no polished version. Just the raw truth of who you become when nobody’s watching.

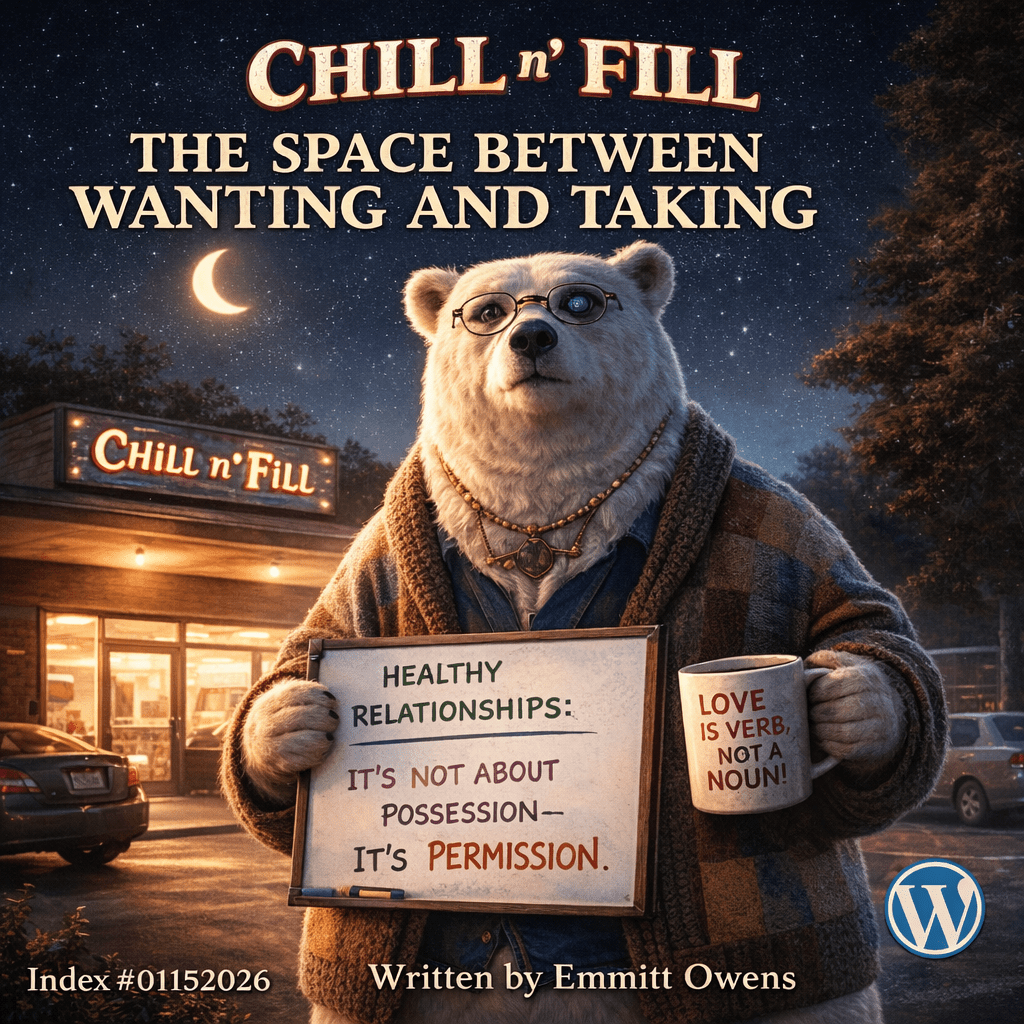

I looked up from reorganizing the gum display (Bob had arranged it by “emotional impact” rather than brand, which meant Big Red was next to Orbit because they both “represented commitment”) to lock eyes with our twenty-foot polar bear mascot, dressed like it was about to recommend boundaries and active listening.

Bob had outfitted the massive bear in a cardigan—an actual enormous cardigan that looked like it had been sewn from multiple blankets. Reading glasses hung from a chain around its neck, constructed from hula hoops and magnifying glasses. In one paw, it held a whiteboard, and in the other, a comically oversized coffee mug that read “LOVE IS VERB, NOT NOUN” in shaky hand-painted letters.

The whiteboard declared: “HEALTHY RELATIONSHIPS: IT’S NOT ABOUT POSSESSION—IT’S ABOUT PERMISSION.”

Inside the store, I’d just finished restocking the coffee supplies when Bob’s voice crackled to life over the PA system like a man freshly introduced to philosophy during the graveyard shift.

“Attention Chill n’Fill customers and … Cindy!” Bob’s voice boomed through the fluorescent-lit aisles. “In honor of our Couples Therapist Bear and in recognition that healthy love is about respect, not control, tonight we’re offering a special: Buy any two items that represent trust and get a free pack of mints! Because fresh breath is important, but fresh boundaries are essential! Let the one-eyed polar bear witness your commitment to emotional maturity!”

The intercom cut off with its usual burst of static as Nina Simone’s “I Put a Spell on You” began playing through our ghostly radio system—appropriate for a night about the difference between wanting someone and needing to own them.

Outside, our massive one-eyed polar bear stood tall in the parking lot, its therapist costume catching the harsh glow of the lights. That single mechanical eye—stamped “Cheinco 1957″—looked over the arriving cars as though it had encountered every version of human intimacy and still trusted that people could approach it thoughtfully.

This was either Bob’s most accidentally profound community service project or his way of working through his own relationship questions. Knowing Bob, it was definitely both.

The Long-Distance Couple

The first customer arrived at 12:52 AM—a woman in her late twenties, wearing pajama pants and a University of Alabama sweatshirt, moving through the aisles while engaged in a video conversation. Her phone was upright in her palm, and I could hear a male voice coming through the speaker.

“I’m just grabbing coffee, babe,” she said, navigating the aisles while maintaining eye contact with her screen. “Yeah, the Chill n’Fill. The one with the giant bear.”

She selected coffee, creamer, and a bag of those chocolate-covered pretzels that cost too much but tasted like comfort. The whole time, her phone stayed visible, the man on the screen just… there. Not demanding attention, not asking what she was doing—just present.

“You want me to show you the bear?” she asked, a smile in her voice. “The owner dressed it like a therapist this time. Yeah, I know. He’s committed to his business.”

She walked outside, turning her phone toward our massive polar bear in its cardigan and oversized glasses. I could hear the man laughing—genuine, delighted.

“That’s incredible,” his voice came through. “Tell him he’s brilliant.”

When she came back inside to pay, she was still connected, the man on her screen now apparently reading something on his end.

“Sorry,” she said to me, slightly embarrassed. “We’re long-distance. This is kind of how we hang out.”

“How long?” I asked, scanning her items.

“Two years. He’s in grad school in Michigan, I’m finishing my degree here. Another year and a half until we’re in the same city again.”

From her phone screen, the man’s voice: “You don’t have to explain our whole life story, Emm.”

“I know,” she laughed. “I just like talking about you.”

There was something in that exchange—the ease of it, the lack of defensiveness. She wasn’t proving anything. He wasn’t checking on her. They were just… together, despite the distance.

“Can I ask you something?” I said, curiously. “How do you make that work? The trust part, I mean. Being that far apart.”

She thought about it while pulling out her card. “We decided early on that we either trusted each other completely or we didn’t do this at all. Like, I’m not gonna ask him what he’s doing at 1 AM on a Friday, because I trust that if something important happens, he’ll tell me. And he doesn’t track my location or need me to check in every hour.”

“It sounds simple,” the man’s voice added from the phone, “but it’s actually really hard. You have to choose trust every single day, even when you’re anxious or insecure.”

“And we talk about it,” she continued. “Like, if I’m feeling weird about something, I say it. Not in an accusatory way, just… ‘hey, I’m having feelings about this, can we talk?’ And we do.”

The radio had shifted to Bonnie Raitt’s “I Can’t Make You Love Me”—that meditation on the difference between wanting someone and having them want you back.

“The hardest part,” she said, more to her phone than to me, “is learning that loving someone doesn’t mean needing constant proof that they love you back. Like, I know he loves me. I don’t need him to text me every hour to prove it.”

“And I know she loves me,” he added, “even when we go a few days without a real conversation because life gets crazy. Trust isn’t about perfect communication. It’s about believing the foundation even when the surface is quiet.”

She paid for her items and I handed her two packs of mints—one for qualifying for Bob’s special, one just because this conversation deserved extra freshness.

“You know what though?” she said, pausing at the door. “The distance taught us something we wouldn’t have learned otherwise. Being together isn’t about proximity. It’s about choice. Every day, we choose each other, even though there are a million easier options. That choice matters more than any amount of physical closeness.”

She left with her phone still connected, the man’s voice saying something about making breakfast together over video tomorrow, and it has me thinking about how real intimacy might actually require space—room to breathe, room to trust, room to choose each other freely rather than out of fear or obligation.

The massive bear watched from the parking lot, its oversized whiteboard, used like a notepad, and coffee mug somehow blessing this particular brand of modern love.

The Recovering Addict

Around 1:17 AM, the doors opened to admit a man in his mid-thirties, moving with noticeable restraint. He had a presence… like someone who’d been through something transformative—awake in a way that suggested survival rather than mere consciousness.

He went straight to the cooler, stood there for a long moment looking at the beer or energy drinks—I couldn’t tell, since both were side by side—then deliberately selected a bottle of water instead.

The radio then powered up and Hozier’s “Like Real People Do” crackled to life—that haunting song about not asking questions about the past, about loving someone as they are right now.

He came to the counter with water, a protein bar, and a notebook—college ruled, the kind used for journaling. As I scanned his items, I noticed the coin he was fidgeting with in his left hand. It caught the fluorescent light: six months sober.

“Congratulations,” I said, nodding toward the coin.

He looked surprised, then slightly embarrassed. “Thanks. It’s weird how visible it becomes when you carry it everywhere.”

“Why do you carry it?”

“Reminds me that I can make different choices,” he said simply. “Like just now, I stood in front of those energy drinks for probably two full minutes having a whole conversation with myself.”

“About?”

“About how easy it would be to grab one. How I could justify it—’it’s just caffeine, not alcohol, not drugs, what’s the harm?’ But that’s how it starts. The small justifications. The little compromises with yourself.” He set the coin on the counter between us. “This reminds me that self-control isn’t about deprivation. It’s about self-honesty.”

A woman entered the store, saw him, and her face lit up—but she didn’t rush over. She just gave him a small wave and started browsing, giving him space to finish his transaction.

“Your girlfriend?” I asked.

“Yeah. Sarah. She’s…” he paused, choosing his words carefully. “She’s the first person I’ve dated since getting sober who understands that loving me doesn’t mean rescuing me. She knows I’m working the program, she knows I go to meetings, and she trusts me to do my work without hovering.”

Sarah appeared at his side with a basket full of baking supplies—flour, sugar, vanilla extract. She smiled at him but didn’t interrupt, just stood close.

“She’s teaching me what healthy support looks like,” he continued. “Like, before, in relationships, I’d get resentful when people tried to control my behavior. But Sarah? She just notices. She pays attention without demanding anything.”

“How so?” I asked, inviting him to continue.

Sarah spoke up, her voice gentle. “Like tonight. I knew he was making a late-night run, and I could’ve asked a hundred questions or insisted on coming with him. But that’s not trust. That’s surveillance. So I just said, ‘I’m making cookies tomorrow if you want to help,’ and let him make his own choices.”

He picked up his coin, held it to the light. “The thing about addiction is that it teaches you that temptation and morality are always at war. But what I’m learning in recovery is that it’s not about beating temptation. It’s about being honest with yourself about what you actually want.”

“And what do you want?” I asked.

“I want to be the kind of person who can stand in front of an energy drink cooler at 1 AM and choose water because I respect myself enough to keep promises I made. Not because someone’s watching. Not because I’m afraid of consequences. Because I want the life that comes from those choices.”

Sarah set her baking supplies down next to his items. “I’m proud of you,” she said simply. “Not for resisting temptation. For being honest about it.”

There was something profound in that distinction—celebrating the honesty rather than the outcome, trusting the process rather than demanding perfection.

As I rang them up (they qualified for Bob’s special—their purchases definitely represented trust), the man looked at me seriously.

“You know what’s weird? People think accountability means having someone else keep you in line. But real accountability is being willing to admit to yourself when you’re struggling. Sarah knows that if I’m having a hard night, I’ll tell her. Not because she demands it, but because I know she won’t judge me for it.”

“And when he tells me he’s struggling,” Sarah added, “I don’t try to fix it or control it. I just listen. Sometimes people need to be witnessed, not rescued.”

They left together, not holding hands, just walking side by side—close enough to be connected, far enough apart to each carry their own weight. The kind of intimacy that comes from trusting someone to do their own work while you do yours.

The bear’s enormous cardigan seemed to flutter in the night breeze, its oversized coffee mug catching the parking lot lights like a blessing.

The New Parents

At 2:04 AM, a couple shuffled in with a new parents kind of energy—exhausted beyond reason, moving in a synchronized shuffle that came from weeks of interrupted sleep.

The radio crackled, echoing a feedback squelch that faded into The Luckiest by Ben Folds—that tender meditation on finding the person who makes life’s chaos bearable.

They split up immediately, each taking a different aisle without hesitation. He headed for diapers and formula. She went straight for the coffee and whatever counted as food when you’re too tired to care about nutrition.

I watched them walk the store in this beautiful, unspoken choreography. When she paused in the snack aisle, clearly paralyzed by too many options and too little brain function, he appeared beside her without a word, grabbed the chips she liked, and moved on. When he struggled with the baby carrier strap, she adjusted it from behind without breaking stride in her own shopping.

They met at the counter with their separate baskets, and the baby—who’d been quiet until now—started fussing.

“I’ve got her,” the man said immediately.

“You’ve been holding her for three hours,” the woman countered. “Let me—”

“I’m good,” he insisted, already swaying in that universal parent-bounce.

“Jake,” she said, and there was something in her voice—not anger, not resentment, just pure exhaustion meeting pure care. “Let me hold my daughter.”

He transferred the baby without argument, and I watched the woman’s whole body relax as she settled the baby against her chest.

“Sorry,” she said to me, not quite making eye contact. “We’re still figuring out the balance.”

“Balance?” I asked, scanning their items.

“Of sharing the load without keeping score,” Jake explained, running a hand through his hair. “Like, I know Sarah’s been up more than me this week, so I try to take more of the night shifts. But then she feels guilty about me being tired, so she tries to do more, and we end up in this weird cycle of both of us being exhausted and resentful that the other one won’t let us help.”

Sarah laughed—a slightly manic sound. “It’s the stupidest argument. ‘Let me be more tired!’ ‘No, I insist on being more tired!’ Meanwhile, neither of us are sleeping, and we’re both losing our minds.”

“What changed?” I asked, because something in their energy suggested they’d recently figured something out.

“We stopped trying to be equal,” Sarah said, adjusting the baby. “Not in a bad way. We just accepted that some weeks Jake does more, some weeks I do more, and that’s okay. As long as we’re honest about what we need instead of trying to be martyrs.”

Jake nodded. “Like tonight. I was the one who wanted to make this run because I needed to get out of the house for twenty minutes. I could’ve pretended it was about diapers or formula, but I told Sarah the truth: I was feeling claustrophobic and needed air. And instead of making me feel guilty about it, she just said, ‘Okay, grab me some coffee while you’re out.’”

“And I could’ve resented him for leaving,” Sarah added, “but honestly? I wanted twenty minutes alone with the baby. Not because Jake was doing anything wrong, but because sometimes I just want to hold her without anyone else’s energy in the room. Even energy I love.”

The baby had settled into that milk-drunk sleep that only newborns achieve, her tiny fist curled against Sarah’s chest.

“The therapist we’re seeing,” Jake said, then caught himself. “Sorry, is that weird to just announce?”

“Not at all,” I said, thinking about our giant therapist bear keeping watch outside.

“She told us that intimacy isn’t about never wanting space from each other. It’s about being honest about when you need space and trusting that the other person won’t interpret it as rejection.”

Sarah smiled at her husband. “Like, I love this man more than I thought I could love anyone. But sometimes I look at him eating cereal and I’m so irrationally annoyed that I have to leave the room. And I used to feel terrible about that, like it meant something was wrong with us. But it doesn’t. It just means I’m human and tired and touched-out from a baby who needs me constantly.”

“And when she tells me she needs space,” Jake said, “I try really hard not to take it personally. Because it’s not about me. It’s about her needing to remember who she is outside of being a mom and a wife.”

“The hardest part,” Sarah said, shifting the baby to her shoulder, “is learning that I can need him desperately and still need space from him simultaneously. Like, I need to know he’s there, that he’s committed, that he’s not going anywhere. But I also need him to give me room to fall apart without trying to fix me.”

They paid for their supplies (definitely qualifying for Bob’s special—trust was implicit in every interaction), and as they gathered their bags, Sarah looked at me with tears in her eyes.

“Sorry,” she said, wiping at her face. “I’m so tired I cry at everything. But thank you for letting us just… be messy for a minute.”

“That’s what this place is for,” I said honestly.

Jake paused at the door, turned back. “You know what’s wild? Before the baby, I thought love was about always wanting to be together. But now I understand that real love is about wanting the other person to be okay, even when that means being apart. Sarah’s happiness doesn’t require my constant presence. Sometimes it requires my absence.”

They left together, not touching, just moving in that synchronized shuffle of people who’ve learned to be a team without losing themselves in the process.

The bear watched them load into their car, its therapist costume somehow blessing their honest, imperfect, beautiful attempt at doing this right.

At 2:31 AM, Bob emerged from his office holding a book I’d never seen before—something about attachment theory and emotional intelligence.

“You know, Cindy,” he said, setting the book on the counter, “I’ve been thinking about relationships.”

“The bear costume tipped me off,” I replied.

“People think love is about finding someone who completes you,” he continued, apparently working through something in real-time. “But what if it’s actually about finding someone who trusts you to complete yourself?”

He gestured out toward the parking lot, where our massive therapist bear stood guard. “That bear knows something we forget: you can love someone fiercely and still give them room to breathe. You can notice everything about them without demanding they explain themselves. You can be present without being possessive.”

“When did you become a relationship philosopher?” I asked.

“Around six o’clock yesterday morning, after a discussion with my wife about how I’d decorate the bear for the week. Apparently.” He picked up his book again. “But seriously—every customer tonight was demonstrating some version of the same thing. Love isn’t about ownership. It’s about creating space for someone to be fully themselves, even when that self doesn’t always include you.”

He wandered back toward his office, leaving me alone with the radio, which had suddenly shifted to Ray LaMontagne’s “You Are the Best Thing”—that celebration of love that’s specific and chosen rather than desperate and clingy.

I walked outside for a moment, standing under our ridiculous therapist bear, looking up at the clear night sky. The air was cool and still, and somewhere in the distance I could hear the highway—all those people moving through the darkness, carrying their own versions of love and longing.

The bear’s single mechanical eye seemed to wink—or maybe that was just the parking lot lights reflecting off the “Cheinco 1957” stamp. Either way, it felt like a benediction.

I thought about the long-distance couple choosing trust over surveillance, the recovering addict learning that self-honesty was more important than perfection, the new parents discovering that real partnership meant making space for individual needs within shared life.

Three different relationships, three different challenges, but the same underlying truth: love isn’t about possession or control. It’s about creating enough safety that the other person can be honest about their struggles, enough trust that distance doesn’t breed suspicion, enough presence that absence doesn’t feel like abandonment.

The night was quieting down, settling into that deep-sleep phase before dawn started threatening the horizon. I went back inside, poured myself a cup of coffee, and sat with the radio as it played through the static—all the ways people try to love each other: the desperate ways, the healthy ways, the messy in-between ways that most of us actually live. I waited for the next person to walk through the doors, trusting the radio to do what it always did.

Bob’s whiteboard message stared at me from the bear’s neck: “HEALTHY RELATIONSHIPS: IT’S NOT ABOUT POSSESSION—IT’S ABOUT PERMISSION.”

Permission to be human. Permission to need space. Permission to struggle. Permission to be honest about temptation without fearing judgment. Permission to choose each other every day without that choice being mandated by fear or obligation.

Maybe that was the real miracle—not that people loved each other, but that they learned to love each other well. With ethics and thoughtfulness. With accountability and self-honesty. With enough trust to let go and enough care to stay close.

Just another night at Chill n’Fill, where a giant polar bear in a cardigan and reading glasses kept watch over the parking lot, blessing everyone brave enough to love someone without needing to own them.

Because that’s what it all came down to—the space between wanting and taking, between caring and controlling, between being together and being consumed.

The radio played on, and I stayed behind that counter bearing witness to all the ways people tried to get it right, one midnight confession at a time.

Leave a comment