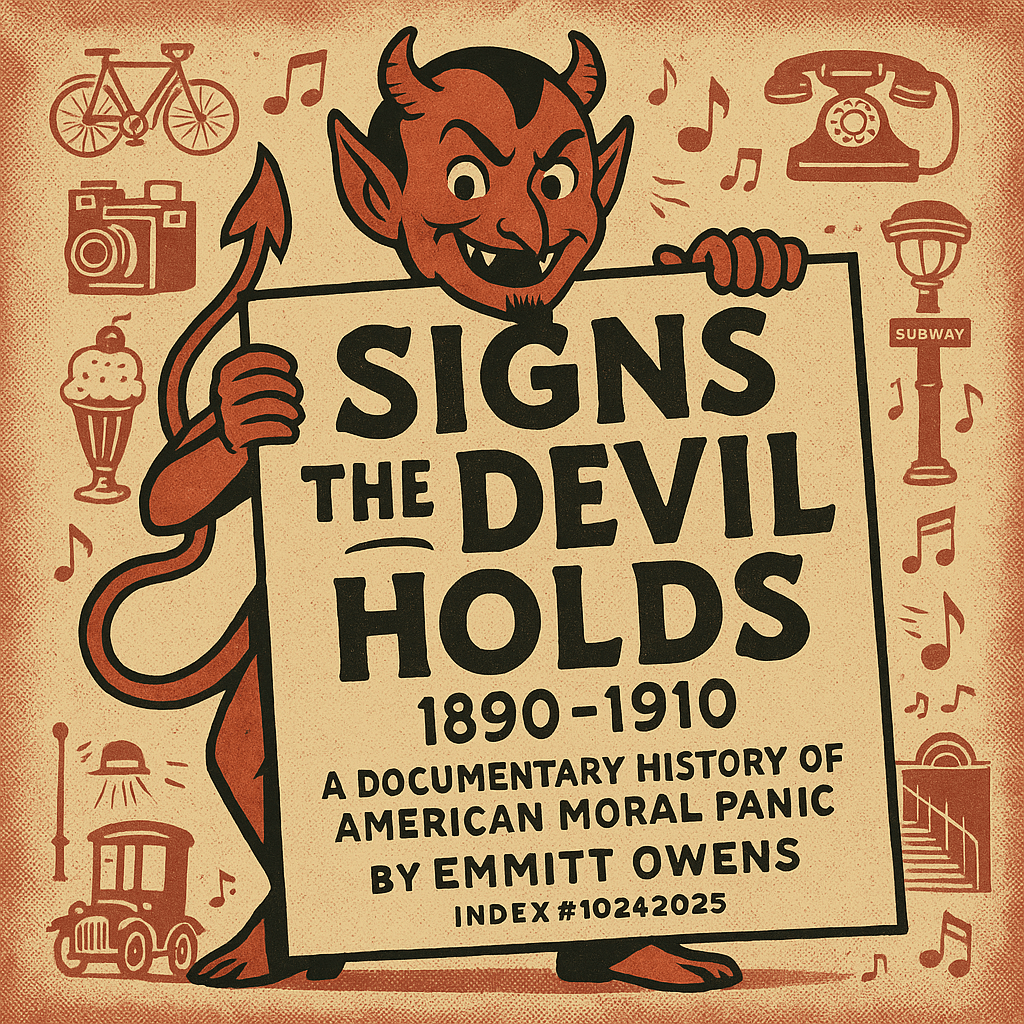

Signs the Devil Holds: 1890-1910

By: Emmitt Owens

(Index #10282025-10292025)

A Documentary History of American Moral Panic

Between 1890 and 1910, Americans identified at least ten distinct signs of Satan’s work on Earth: electricity, women on bicycles, portable cameras, ice cream sodas, telephones, automobiles, penny dreadfuls and dime novels, “white slavery,” ragtime music, and the waltz.

This isn’t speculation. It’s documented in newspaper articles, medical journals, legislative records, religious sermons, and actual federal laws. Real diseases were invented. Real cables were stretched across roads to stop the machines. Real people went to prison. Real legislation is still on the books today.

Here’s what happened.

1. Electricity (1889-1900s): “The Unrestrained Demon”

In 1889, a political cartoon circulated showing a man tangled in electrical wires, apparently dead, while people below either collapsed or fled in terror. The image was titled “The Unrestrained Demon.”

The demon was electricity.

This wasn’t entirely paranoia. On October 11, 1889, a linesman named John Feeks touched a high-voltage line in Manhattan. His body caught fire. He hung tangled in the wires for approximately one hour while a crowd watched from below. Firemen eventually cut him down.

The incident sparked what became known as the New York “wire panic.” The Harper’s Weekly reported on December 14, 1889: “Nearly every wire you see in the open air is thick enough and strong enough to carry a death-dealing current. As things are at present, there is no safety, and danger lurks all around us. It may never reach you, or you may go on for years unhurt, but when the moment comes you are killed instantly. You may touch a wire with your finger, and, though you be on the tenth floor of a building, you may be killed instantly.”

But the fears went beyond legitimate safety concerns about high-voltage lines.

In Sweden, preachers declared the telephone—which required electrical wiring—to be “the instrument of the Devil.” People feared that telephone lines were conduits for evil spirits. Some believed that touching the devices would deliver electric shocks. Telephone poles were vandalized, and in at least one town, it was difficult to find anyone willing to work at the telephone station due to widespread concern about the spiritual danger posed by electricity.

By the early 1900s, electricity had become directly associated with death and obscure evil forces in the public imagination. This represented a significant shift: in earlier centuries, electricity had been connected with divine healing and natural wonder. Now it was the domain of demons.

The paranoia faded as electrical infrastructure became commonplace. We kept using it.

—

2. Women on Bicycles (1890s-1900s): “The Devil’s Chariot”

When the “safety bicycle” was developed in the mid-1880s—the modern two-wheeled design with equal-sized wheels—it became wildly popular. By 1889, approximately 200,000 bicycles were produced annually. Ten years later, that number exceeded 1,000,000.

Women took to cycling enthusiastically. This created a problem.

In rural areas of the Ottoman Empire, Iran, and Central Asia, bicycles were called “şeytan arabası”—the “devil’s cart” or “devil’s chariot.” Conservative religious scholars and fundamentalists opposed cycling, particularly for women, claiming it would harm reproductive organs, embolden sexual permissiveness, and lead to the destruction of the family.

According to Professor Alon Raab of UC Davis, women’s cycling in these regions was attacked as “bid’ah”—any technical innovation deemed heretical. Female cyclists faced not only media criticism and legal restrictions, but physical assaults.

In the West, the panic took a medical turn.

Doctors warned that bicycling could cause a range of newly invented conditions:

– Bicycle Face: described as “usually flushed, but sometimes pale, often with lips more or less drawn, and the beginning of dark shadows under the eyes, and always with an expression of weariness.” Another physician specified “an anxious look and an unwholesome pallor,” along with a clenched jaw and bulging eyes.

– Bicycle Foot

– Bicycle Hand

– Bicycle Back

– Uterine displacement (rendering women incapable of childbearing)

– Hardening of abdominal muscles (causing problems during labor)

– Jarring, jolting, and spinal shock

– Body deformities

– Nervous prostration

Medical journals published detailed warnings about how bicycle saddles could be used for masturbation. One physician wrote: “The saddle can be tilted in every bicycle as desired… In this way a girl… could, by carrying the front peak or pommel high, or by relaxing the stretched leather in order to let it form a deep, hammock-like concavity which would fit itself snugly over the entire vulva and reach up in front, bring about constant friction over the clitoris and labia.”

This wasn’t a concern about sexual health. It was about sexual morality. Young women were supposed to be chaste and pure, and the bicycle threatened to awaken sexual feelings that would destroy gender definitions and moral order.

The bicycle also required practical clothing adjustments. Long skirts could get caught in pedals and wheels. Many women adopted bloomers—loose-fitting pants. This was seen as too close to men’s clothing, representing a dangerous blurring of gender boundaries. Some argued that unchaperoned bicycling was a “slippery slope to sex work.”

Bicycling was claimed to “disgrace a woman’s walk, turning it into a plunging kind of motion.” The exertion would turn delicate female bodies “much too masculine for the times.”

In the 1890s, these concerns constituted a full-scale moral panic in both America and Britain. The panic eventually subsided as cycling became commonplace.

Women kept riding bicycles. Many of them wore pants.

—

3. Kodak Cameras (1888-1900s): “The Kodak Fiend”

In 1888, George Eastman introduced the Kodak camera. It was portable, relatively inexpensive ($25 = about $700 in today’s dollars), and simple to use. Customers could take pictures and mail the camera back to Kodak for development. “You press the button,” the ads promised, “we do the rest.”

By 1900, Eastman released the Kodak Brownie for $1 (equivalent to about $33 today). The name referenced both its designer, Frank A. Brownell, and magical characters from popular children’s books. It was marketed directly to children. “Plant the Brownie acorn and the Kodak oak will grow,” read one slogan.

In the first year, Kodak shipped more than 1.5 million Brownies.

Almost immediately, photographers were labeled “Kodak fiends.”

In 1890, The Hawaiian Gazette published a piece titled “The Kodak Fiend”: “Have you seen the Kodak fiend? Well, he has seen you. He caught your expression yesterday while you were talking at the Post Office. He has taken you at a disadvantage and transfixed your uncouth position and passed it on to be laughed at by friend and foe alike. His click is heard on every hand. He is merciless and omnipresent and has as little conscience and respect for proprieties as the veriest hoodlum.”

Newspapers across the country cautioned Americans to “beware the Kodak,” calling the cameras “deadly weapons” and “deadly little boxes.”

The cameras were banned from businesses, beaches, and the Washington Monument.

In Britain, young men formed “Vigilance Associations” with the stated purpose of “thrashing the cads with cameras who go about at seaside places taking snapshots of ladies emerging from the deep.”

President Theodore Roosevelt was “known to exhibit impatience on discovering designs to Kodak him.” During his first week in office, a 15-year-old boy attempted to photograph him leaving church. Roosevelt ordered a police officer to block the camera and, as reported in the New York Times, exclaimed: “You ought to be ashamed of yourself! Trying to take a man’s picture as he leaves a house of worship. It is a disgrace!”

Reginald Claypoole Vanderbilt allegedly horsewhipped a man who took his photograph without permission.

The panic centered on privacy. Prior to portable cameras, except for a handful of eyewitnesses, public behavior was effectively private. The camera changed that permanently. Anyone could now be photographed at any time without consent.

In 1890, Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis published their influential article “The Right to Privacy” in the Harvard Law Review, directly responding to the Kodak phenomenon: “Instantaneous photographs and newspaper enterprise have invaded the sacred precincts of private and domestic life…the latest advances in photographic art have rendered it possible to take pictures surreptitiously.”

The privacy concerns were legitimate. What was less legitimate was treating photographers as demonic “fiends” requiring vigilante violence.

By 1910, the panic had subsided. Photography became ubiquitous. The legal frameworks Warren and Brandeis helped establish remain foundational to privacy law today.

Everyone has a camera now. Most people carry one in their pocket at all times.

—

4. Ice Cream Sodas (1890s-1900s): “Gateway to Alcoholism” and “Spider’s Web”

The ice cream soda was invented in 1874 by Robert Green at the Franklin Institute’s exhibit in Philadelphia. It was a simple combination: soda water, syrup, and ice cream. People loved it.

The Women’s Christian Temperance Union did not.

The WCTU, which had organized in 1873 primarily consisting of women from the Methodist Episcopal Church, campaigned against ice cream sodas with the same intensity they brought to actual alcohol. The fizzy, sweet drinks were described as “training wheels for alcoholism.” The concern was that ice cream sodas would create a taste for more dangerous substances.

Some communities became convinced that the drinks were gateway drugs.

Multiple states and municipalities banned the sale of ice cream sodas on Sundays. This included Evanston, Illinois; multiple locations in Massachusetts; and Huron, South Dakota. The reasoning was that these parlors were “hotbeds of temptation and vice”—places where young men and women could mingle unsupervised. Ordering an ice cream soda on the Sabbath was considered morally corrupt, comparable to smoking a cigar in the church choir.

But the fears went darker than mere Sabbath-breaking.

By the late 1900s, ice cream parlors had become directly implicated in the “white slavery” panic that was sweeping the nation. A typical warning from the period stated: “One thing should be made very clear to the girl who comes up to the city, and that is that the ordinary ice cream parlor is very likely to be a spider’s web for her entanglement. This is perhaps especially true of those ice cream saloons and fruit stores kept by foreigners. Scores of cases are on record where young girls have taken their first step towards ‘white slavery’ in places of this character.”

Ice cream parlors, particularly those owned by immigrants, were now seen as recruitment centers for sex trafficking rings. The sweet, innocent ice cream soda had become a lure used by predators to trap young women.

Technically, you could eat ice cream at home on Sundays. But the moment you added fizzy seltzer to the mix—or went to a parlor where foreigners might drug you—you were living in sin or courting abduction.

Soda fountain operators found a workaround: they created a new dessert with ice cream, syrup, and toppings—but no carbonation, and therefore technically not an ice cream “soda.” They served it on Sundays.

They called it a “sundae.”

The panic about ice cream sodas was ironic, because when Prohibition was enacted in 1920, ice cream consumption exploded. Breweries that could no longer produce alcohol pivoted to ice cream production. Anheuser-Busch sold ice cream with the slogan “eat a plate of ice cream every day.” Bars were converted to soda fountains and ice cream parlors.

Between 1916 and 1925, ice cream consumption in the United States increased by 55 percent—while the population only increased about 15 percent. By 1922, Americans consumed 325 million gallons of ice cream annually. A Wichita ice cream manufacturer declared that “Prohibition made the chocolate ice cream soda the national drink.”

The substance the WCTU feared as a gateway to alcoholism became the replacement for alcohol.

We still eat ice cream. We still drink soda. Neither one led to the moral collapse of American society.

—

5. Telephones (1900s): “The Instrument of the Devil”

The telephone was not greeted with universal enthusiasm.

In Sweden, preachers declared it “the instrument of the Devil.” The concern was that telephone lines could attract evil spirits or, at minimum, lightning. In at least one Swedish town, it became difficult to find premises for a telephone station or to recruit a manager, due to widespread fear about the spiritual danger posed by telephone lines and the electricity running through them.

Farmers, landowners, and property owners sometimes refused to allow telephone lines to pass over their land or buildings. Some pulled down lines and destroyed them.

Beyond spiritual concerns, there were social ones. Some elderly people feared that touching the telephone would deliver electric shocks. Men worried that their wives would waste too much time gossiping on the device.

None of these fears stopped telephone adoption. The practical utility of instant voice communication across distances proved too valuable.

People kept using telephones. Many conversations were, in fact, gossip.

—

6. Automobiles (1900-1920): “Devil Wagons”

Around 1900, there were approximately 100 different brands of “horseless carriages” being marketed in the United States. Since they were virtually handmade, they were outrageously expensive—perceived as “no more than a high-priced toy for the rich” and “a despicable symbol of arrogance and power.”

They were also called “Devil Wagons.”

In rural America and parts of Canada, the term was used earnestly. The machines were loud, smelled foul, produced clouds of dust, and terrified horses. A Catholic priest gave sermons about “auto madness.” Churches blamed automobiles for declining Sunday attendance—families went “Sunday motoring” instead of attending Mass.

The Chicago Tribune ran a headline asking: “Is Automobile Mania a Form of Insanity?”

In 1902, Chicago Mayor Carter Harrison complained: “The other day on one of the North Side boulevards, I heard a toot that seemed right behind me. I jumped about six feet and then looked around. The machine was fully a half-block away, and when it went past, all the occupants grinned as if it were a good joke. These fellows blow their horns just to see the people jump, I believe.”

Fast drivers were called “scorchers” or “Auto Fiends.” The phrase “auto fiend” appeared frequently in early 1900s journalism. From The Motor journal in 1902: “It was here that an automobile fiend, pressing his horrible squeaker [horn], came on heedless of everybody and cooly ran into the back [of children].”

A 1906 Georgia Court of Appeals ruling stated that automobiles were to be treated as “ferocious animals,” and “the laws relating to the duty of owners of such animals is to be applied.”

Dean Howard McClenahan at Princeton blamed “the gasoline motor car” for the Jazz Age’s “steep decline in moral standards.” Sunday motoring left churches deserted. Youth were “shamelessly petting.” Speakeasies disguised as hot-dog stands beckoned down country lanes.

Multiple jurisdictions passed laws attempting to control or ban automobiles:

– Vermont passed a law requiring a person to walk in front of the car waving a red flag.

– In Glencoe, Illinois, someone stretched a length of steel cable across a road in an effort to stop “the devil wagons.”

– Some cities banned automobiles outright.

– Prince Edward Island banned automobiles from public roads in 1908. There were only seven cars on the roads at the time. The ban lasted until 1913, when cars were permitted three days per week.

– Connecticut passed America’s first speed limit in 1901: 12 mph in cities, 15 mph in the country.

Religious opposition characterized cars as “fire-breathing metal demons carrying souls to hell at thirty miles per hour.”

One town in Pennsylvania allegedly required drivers to “send up a rocket every mile” when operating their vehicles.

By 1920, the panic had largely subsided. Cars were too useful. The infrastructure adapted. Speed limits, traffic signals, driver’s licenses, and traffic laws were developed. Churches stopped blaming cars for moral decay and started hosting parking lots.

Today, there are approximately 276 million automobiles registered in the United States.

Nobody stretches steel cables across highways anymore. The devil moved on to other things.

—

7. Penny Dreadfuls and Dime Novels (1840s-1900s): “Printed Poison”

Long before anyone worried about violent video games or comic books, there were penny dreadfuls and dime novels—cheap pulp fiction that was going to destroy an entire generation.

Penny dreadfuls appeared in Britain in the 1830s and 1840s: luridly illustrated gothic tales printed on cheap pulp paper, sold for just a penny. With titles like “Varney the Vampire” and “Sweeney Todd: the Demon Barber of Fleet Street”, they were wildly popular with young male readers. The American equivalent was the “dime novel” (which usually cost a nickel)—adventure stories about outlaws, detectives, and Western heroes.

By the 1880s and 1890s, a full-blown moral panic had erupted.

Newspapers and magazines gave countless examples of boys who, after reading a penny dreadful, had robbed their employer or embarked on criminal enterprise. An 1895 edition of The Speaker told of a “half-witted boy” who, after reading many penny dreadfuls, killed his mother. An 1896 edition of the Dundee Courier attributed the suicide of a fourteen-year-old London errand boy to the negative effects of reading “penny horribles.”

In the United States, teenage serial killer Jesse Pomeroy was described as “a close reader of dime novels and yellow covered literature, until his brain was turned.” His trial argued that reading about “Texas Jack” was his “highest ambition.” Newspapers warned that Pomeroy’s brutality was “what came of reading dime novels.”

The panic reached its peak in 1892, when the suicide of a 12-year-old boy was attributed to “temporary insanity, induced by reading trashy novels.”

The most sensational case came in 1895, when the body of Emily Coombes was discovered in her East London home. She lived there with her two sons, Robert (13) and Nathaniel (12). When police investigated, they found a collection of penny dreadfuls in the parlor. These were quickly entered into evidence at the inquest. The press latched onto this detail, and the story reignited the national debate over juvenile crime and sensational literature.

Critics described penny dreadfuls as “printed poison.” One magistrate claimed: “It is almost a daily occurrence with magistrates to have before them boys who, having read a number of ‘dreadfuls’, followed the examples set forth in such publications, robbed their employers, bought revolvers with the proceeds, and finished by running away from home, and installing themselves in the back streets as ‘highwaymen’. This and many other evils the ‘penny dreadful’ is responsible for. It makes thieves of the coming generation, and so helps fill our gaols.”

The books themselves were typically about eight pages long, featuring sensational stories of crime, detection, supernatural entities, and adventure. Some Victorian educators claimed they glamorized crime. Others argued that they encouraged working-class youths to be dissatisfied with “the mundanity of their day-to-day lives and to aspire to riches and adventure outside their class.”

Many urged that the publication and consumption of penny dreadfuls be criminalized.

In reality, studies found that violent crime actually decreased throughout the 19th century. The books were “overdramatic and sensational but generally harmless.” If anything, the cheap literature resulted in “increasingly literate youth in the Industrial period.”

The panic eventually subsided as new forms of entertainment emerged. The stories didn’t disappear—they evolved into the detective novels, horror fiction, and thrillers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Today, the characters once vilified as corrupting influences—Sweeney Todd, Dracula, Sherlock Holmes—are considered classics of literature and entertainment.

Nobody blames murders on dime novels anymore. We moved on to blaming comic books, then heavy metal, then video games.

—

8. “White Slavery” (1907-1910): The Spider’s Web

By 1907, a full-fledged moral panic had seized America: the belief that vast organized networks of traffickers—primarily immigrants—were kidnapping, drugging, and forcing white American girls into prostitution.

This was called “white slavery.”

The term had originated in the 1840s, borrowed from abolitionist Charles Sumner’s description of the Barbary slave trade. But by the early 1900s, it had evolved into something far more sinister in the American imagination: a widespread conspiracy to corrupt and enslave innocent white girls.

Muckraking journalists fueled the hysteria with sensationalized stories. George Kibbe Turner, writing in McClure’s Magazine in 1907, claimed that “a loosely organized association… largely composed of Russian Jews” was the primary source of supply for Chicago brothels.

Edwin W. Sims, U.S. District Attorney in Chicago, claimed to have proof of a nationwide white slavery ring: “The legal evidence thus far collected establishes with complete moral certainty these awful facts: that the white slave traffic is a system operated by a syndicate which has its ramifications from the Atlantic seaboard to the Pacific Ocean, with ‘clearinghouses’ or ‘distribution centers’ in nearly all of the larger cities; that in this ghastly traffic the buying price of a young girl is from $15 up and that the selling price is from $200 to $600.”

Popular books appeared with titles like Fighting the Traffic in Young Girls: Or, War on the White Slave Trade, warning parents about the supposed dangers of living or working in cities, taking public transportation alone, visiting ice cream parlors or restaurants, and congregating in dance halls—which one essayist called “truly the ante-room to hell itself.”

Young women were told that danger lurked everywhere. As previously noted, ice cream parlors—especially those “kept by foreigners”—were described as “spider’s web[s]” where “young girls have taken their first step towards ‘white slavery.’”

The committees appointed to investigate believed that “no girl would enter prostitution unless drugged or held captive.”

In reality, local vice commissions found that prostitution was “overwhelmingly locally organized without any large business structure, and willingly engaged in by the prostitutes.” As feminist Emma Goldman observed at the time: “Whether our reformers admit it or not, the economic and social inferiority of woman is responsible for prostitution.”

But reality didn’t matter. The panic had taken hold.

On June 25, 1910, Congress passed the White Slave Traffic Act—better known as the Mann Act—making it a federal crime to transport any woman or girl across state lines “for the purpose of prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose.”

That last phrase—”for any other immoral purpose”—would prove to be the most problematic. The law was used to prosecute consensual sexual activity, premarital sex, extramarital affairs, and most insidiously, interracial relationships.

Jack Johnson, the first Black heavyweight boxing champion, was one of the Mann Act’s first and most famous victims. When he beat white champion James J. Jeffries in 1910, it triggered race riots. The public felt “the champion was such a bad character that it was their obligation to destroy him by any means available.”

In 1912, Johnson was prosecuted under the Mann Act for his relationships with white women. An all-white jury convicted him based on testimony from Belle Schreiber, a white prostitute and his former girlfriend, and his recent marriage to another white woman, Lucile Cameron. He was sentenced to a year and a day in prison. Johnson fled to Europe and lived in exile for seven years.

As a direct result of the case’s notoriety, lawmakers introduced bills to ban marriage between Black and white people in multiple states.

The Mann Act remained on the books largely unchanged until 1986. It was used for decades to prosecute people—particularly Black men—for consensual relationships that offended white moral sensibilities. In 2018, 72 years after his death, Jack Johnson was posthumously pardoned by President Trump for what was described as a “racially-motivated injustice.”

While prostitution and trafficking were real problems, the “white slavery” panic massively exaggerated the threat, blamed immigrants and racial minorities, and led to legislation that was weaponized against the very people it claimed to protect.

The Mann Act is still federal law. It has been amended, but it remains.

—

9. Ragtime Music (1890s-1910s): “The Ragtime Evil”

In the 1890s, a new kind of music emerged from Black communities in the Midwest—particularly in the Chestnut Valley red-light district of St. Louis. It featured syncopated rhythms, percussive piano, and an infectious, joyful energy that made people want to move.

It was called ragtime. And it was going to destroy America.

As ragtime spread from St. Louis to Chicago, Kansas City, and eventually across the nation and into Europe, white America’s moral guardians became increasingly alarmed. The music was transformational and disruptive—much as rock and roll would be in the 1950s. It was “a hot, rude new sound that erupted out of the black underclass to the delight of young white people desperate to break away from stifling Victorian propriety.”

Composer Edward MacDowell called it “whorehouse music.”

The New York Herald asked: “Can it be said that America is falling prey to the collective soul of the negro through the influence of what is popularly known as ragtime music?”

A letter published in The Musical Courier stated: “The American ‘rag time’ evolved music is symbolic of the primitive morality and perceptible moral limitations of the negro type. With the latter sexual restraint is almost unknown, and the widest latitude of moral uncertainty is conceded.”

This wasn’t just musical criticism. It was explicitly racial panic about Black cultural influence on white America. Ragtime’s Black heritage was common knowledge, and as white Americans embraced it, “America’s moral standard bearers viewed themselves in a battle for national purity of race and the health of the moral fabric.”

References to moral decay became standard in ragtime criticism. A 1914 editorial declared: “Let us take a united stand against the Ragtime Evil as we would against bad literature, and horrors of war or intemperance and other socially destructive evils. In Christian homes, where purity and morals are stressed, ragtime should find no resting place. Avaunt the ragtime rot! Let us purge America and the Divine Art of Music from this polluting nuisance.”

Canon Newboldt of St. Paul’s Cathedral in London condemned ragtime’s associated dances, asking: “Would indecent dances suggestive of evil and destructive of modesty disgrace our civilization for a moment if professed Christians were to say: I will not allow my daughter to turn into Salome?”

The New York Times supported Newboldt’s denunciation in 1913, lending legitimacy to the panic. Religious virtue became associated with shunning ragtime music. If critics warned of the danger of even listening to ragtime, one could only imagine what they thought of those who performed it—or the ethnic group that created it.

The criticisms weren’t just moral—they were pseudo-medical. Critics argued that ragtime was “all rhythm and no melody,” and that African-influenced music’s emphasis on rhythm was physically dangerous. Some doctors reported that “wild rhythms” could cause irregular heartbeat. Others warned that ragtime offered “musical ‘cheap thrills’” that would hurt listeners’ ability to appreciate “good” music.

Ragtime was blamed for everything from race riots to domestic violence to general dissatisfaction with life. Its lyrics—often written by Black composers in the minstrel show tradition—spoke with disdain about monogamous relationships and regular jobs, evoking “a world of easy sexuality and quick violence.”

Some Black Americans also criticized ragtime, though for different reasons. They worried it was “the worst sort of primitive expression that impeded their collective progress as a people.” Middle-class African Americans sometimes agreed with white critics that jazz’s “improvised rhythms and sounds were promoting promiscuity.”

The panic persisted through the 1910s. Ragtime was associated with prostitution (the music was born in red-light districts), racial mixing, moral corruption, and the breakdown of social order.

By the 1920s, ragtime had evolved into jazz—which would spark its own moral panic, with familiar accusations about “devilish rites” and “negroid mating games.”

Today, Scott Joplin’s “The Entertainer” and “Maple Leaf Rag” are considered classics of American music. Ragtime is taught in music schools. Its syncopated rhythms influenced jazz, blues, and virtually all American popular music that followed.

The devil’s music became America’s music. And we kept right on dancing to it.

—

10. Dance Halls and the Waltz (1890s-1910s): “The Ante-Room to Hell”

By the 1890s and 1900s, the waltz—which had sparked its own moral panic decades earlier—was being joined by new, even more scandalous dances. Dance halls became sites of intense moral concern, described as places where young people (particularly women) were exposed to corruption, vice, and “white slavery” recruiters.

The waltz itself had been controversial since its introduction to England and America in the early 1800s. Unlike previous dances where couples stood side by side, the waltz required partners to face each other, hold each other close, and whirl through rapid turns. This physical intimacy was shocking.

Lord Byron—himself notorious for his outrageous private life—disapproved of the waltz. The Times of London was horrified when it appeared at a royal ball in 1816, calling it an “indecent foreign dance”: “National morals depend on national habits: and it is quite sufficient to cast one’s eyes on the voluptuous intertwining of the limbs, and close compressure of the bodies, in their dance, to see that it is indeed far removed from the modest reserve which has hitherto been considered distinctive of English females.”

Madame Celnart, author of The Gentleman and Lady’s Book of Politeness (1833), was succinct: “The waltz is a dance of quite too loose a character, and unmarried ladies should refrain from it altogether. Both in public and in private.”

The waltz’s effects were seen as most dangerous to young women. Donald Walker wrote in Exercises for Ladies (1836) that vertigo was “one of the great inconveniences of the Waltz,” and: “the character of this dance, its rapid turning, the clasping of the dancers, their exciting contact, and the too quick and too long successions of agreeable emotions, produce sometimes in women of irritable constitution, syncopes, or fainting spells, spasms, and other accidents which should induce them to renounce it.”

By the 1890s and 1900s, the waltz had been joined by the cakewalk (derived from slave plantation dances), and soon would be followed by the turkey trot, the grizzly bear, the bunny hug, and other “animal dances.” All were condemned as immoral.

Dance halls—places where young men and women could gather without strict chaperonage—were particular targets of moral reformers. As noted in Fighting the Traffic in Young Girls, dance halls were described as “truly the ante-room to hell itself.”

Progressive Era reformer Jane Addams believed dance halls were “one of the great pitfalls of the city.” During World War I, middle-class women formed “morals patrols” to police public morals, particularly targeting young working-class women who were “swooning for men in uniform.”

The concern was always the same: unsupervised young people, physical contact, rhythmic movement, and the possibility of sexual awakening outside the bounds of marriage.

Around 1900, when ragtime began to influence American dance, the panic intensified. The new dances from America were described as “negroid mating games” or “devilish rites.” A Swedish warning from the 1920s noted that “the young lost sight of proper morality by taking part in, and performing, these” dances.

The waltz—once scandalous—was now refined and respectable compared to these new horrors.

By 2010, the Swedish Crown Princess Victoria married Prince Daniel, and at the wedding party, they started the dancing with a waltz. In 200 years, the waltz had gone from immoral corruption to the prime wedding dance accepted throughout society.

People kept dancing. The devil moved on to jazz, then rock and roll, then hip-hop.

The ante-room to hell is now just called a nightclub.

—

11. The Boston Subway (1897): “The Infernal Hole”

On September 1, 1897, Boston opened America’s first subway. More than 100 people crowded onto the first train at 6 AM to travel through a tunnel under downtown. By the end of the day, over 100,000 people had taken the three-and-a-half minute trip.

Many people didn’t want to take that trip at all.

At the time, traveling underground carried a powerful psychological stigma. Many people associated the subterranean world with death, decay, and evil spirits. As Boston historian Charles Bahne notes, the underground was considered “the realm of Lucifer himself, inhabited by lost souls, moldering corpses, strange forms of animal life, and noxious vapors.”

The newly formed Anti-Subway League argued that the project posed serious threats to public health. Mold, mildew, and germs would infect commuters with respiratory ailments. Rodents and snakes would be driven to the surface and plague the city. The Boston Post supported these claims with sensationalist editorials, running headlines like “Hideous Germs Lurk in Underground Air” accompanied by illustrations of scary-looking “subway microbes.”

Historian Stephen Puleo explains the resistance: “Folks felt like traveling underground was very close to the netherworld, that you were getting closer to the devil, that you were taking this great risk in God’s eyes by traveling on a subway.”

A petition signed by 12,000 businessmen opposed the subway. Streets would be torn up. Sewer systems, water lines, and electrical lines would be affected. But beyond practical concerns, there was genuine spiritual fear about descending into the earth.

The fears seemed justified when construction began. During the first weeks of digging, a water main ruptured and the nearby Park Street Church was covered with mud and debris. Preaching from the pulpit, the pastor damned the project site, referring to it as the “infernal hole” and an “un-Christian outrage.” He concluded his sermon by asking congregants: “Who is the boss in charge of the work? It is the Devil!”

Then came an even more disturbing discovery.

The first section was laid out along the edge of the Old Common Burial Ground. Workers expected to see a few gravestones. Instead, they eventually unearthed the remains of over 900 unmarked graves from the Revolutionary War era. Nearly seventy-five boxes—each containing a miscellaneous assortment of bones—were prepared and eventually buried in a mass grave. The site is marked by a tablet reading: “Here Were Re-interred the Remains of Persons Found Under the Boylston Street Mall During the Digging of the Subway, 1895.”

Six months before the scheduled opening, on March 4, 1897, disaster struck. A spark from a streetcar ignited gas leaking from a damaged pipe at the corner of Boylston and Tremont Streets. The explosion killed nine men.

The project seemed cursed. The stigma of death tainted public perception of the subway so deeply that even the station entrances were criticized for their “tomb-like” appearance. According to one critic quoted in the New York Sun: “They somewhat resemble the plainer types of mausoleums that are seen in the cemeteries of Paris.”

To calm public fears about traveling underground, city officials took specific measures: the tunnel’s interior was painted white and lit up by electric lamps placed every few feet. The goal was to make the underground space as unlike the realm of darkness as possible.

When the subway finally opened on September 1, 1897, headlines read “First Car Off the Earth”—as if the train were launching into space rather than descending beneath the streets. Despite lingering fears, more than 250,000 Bostonians rode the underground rails on its first day. Most marveled at the new wonder.

Within four hours, there was an incident: subway car No. 2022 clipped a crossbeam while emerging from the tunnel. But the car continued safely, and riders kept coming.

By 1904, New York opened nearly nine miles of subway. Philadelphia followed between 1905 and 1908. The practical utility of underground transit overcame the fear of descending into what many still considered the devil’s domain.

Today, the MBTA serves over 1.3 million passengers daily across the system. Nobody worries about getting closer to hell by taking the T—though riders might use colorful language about delays.

The realm of Lucifer became the realm of the morning commute.

—

12. Women Whistling: “The Heart of the Blessed Virgin Bleeds”

In the 1890s and early 1900s, women who whistled were not just considered unladylike—they were considered cursed.

The old saying went: “A whistling woman and a crowing hen comes to no good end.”

This wasn’t just a quaint folk belief. It was taken seriously enough that women were actively discouraged—sometimes forcefully—from whistling at all. According to one legend, the taboo originated during the crucifixion: while the nails for Christ’s cross were being forged, a woman stood by and whistled. Her action was so offensive that it cursed all women who whistled thereafter.

In 1879, a correspondent to Notes and Queries related an incident where his wife tried to coax their dog by whistling. She was suddenly interrupted by a Roman Catholic servant who exclaimed “in the most piteous accents”: “If you please, ma’am, don’t whistle—every time a woman whistles, the heart of the blessed Virgin bleeds!”

In some districts of North Germany, villagers said that if one whistles in the evening, it makes the angels weep. The natives of Tonga Islands in Polynesia held it to be wrong to whistle, as the act was thought to be disrespectful to God. In Iceland, villagers believed that whistling “scares from him the Holy Ghost.”

Whistling in general was popularly called “the devil’s music”—presumably because when people were up to something wrong and likely to be caught, they assumed an air of indifference by whistling. But the prohibition was particularly strict for women.

Some maintained that the whistler’s mouth could not be purified for forty days. According to others, Satan touching a person’s body caused them to produce this “offensive sound.”

The superstition was so widespread that it’s notable how seldom women of the era actually whistled. Victorian medical authorities noted that whistling could be beneficial for lung development and recommended it—but primarily for boys. One commentator observed: “All the men whose business it is to try the wind-instruments made at the various factories before sending them off for sale are, without exception, free from pulmonary affections.” The same health benefits could have applied to women, but the taboo was too strong.

There was no scientific or medical basis for any harm from women whistling. There was no theological basis either—the crucifixion story was pure legend. But the belief persisted that women who whistled were summoning evil, offending God, or marking themselves for a bad end.

By the 1920s, as women gained suffrage and entered public life, the taboo began to fade. Some women even became professional “whistlers,” performing on the Chautauqua circuit and in vaudeville. The title of a 1924 novel, Whistling Women and Crowing Hens, suggests the saying was still known but becoming outdated.

Today, women whistle freely. The angels have stopped weeping. The Blessed Virgin’s heart has healed. Nobody’s mouth requires forty days of purification.

The hen may crow, the woman may whistle, and the world continues to turn.

—

13. Saying “Damn” and “Devil”: The Unutterable Words

In the Victorian era, certain words were so offensive that they were literally blanked out in print. Books would render them as “d——n” or “d——l,” leaving readers to fill in the profanity for themselves.

The words were “damn” and “devil.”

To modern readers, this seems absurd. These words appear regularly in contemporary speech, media, and literature. But in the late 1800s and early 1900s, when eternal damnation was a constant preoccupation and hell was a very real place in the minds of most Americans, these words carried genuine blasphemous weight.

The offense wasn’t in the words themselves—it was in what they invoked. To say “damn” was to call down eternal damnation on something or someone. To invoke “the devil” was to summon or acknowledge the presence of evil. This wasn’t casual swearing—it was considered a misuse of concepts central to one’s immortal soul.

As one Victorian-era discussion noted: “The man who barks his shin and says ‘Damn that chair’ does not genuinely wish the chair to be endowed with an immortal soul, which should then be consigned to perdition.” The problem was that invoking damnation at all—even casually—was seen as spiritually dangerous.

In Wuthering Heights (1847), Emily Brontë has her narrator note that Heathcliff employed “an epithet as harmless as duck, or sheep, but generally represented by a dash.” Victorian authors routinely blanked out these words, even when their characters—rough types like Heathcliff—would certainly have used them.

Words like “devil” and “damned” were blanked out not only in fiction but in newspaper reports, court transcripts, and other documents. A person who used such language in polite company risked social ostracism. Children who used these words faced severe punishment.

The prohibition was particularly strict for children. When children sang songs containing references to hell or the devil—even in religious contexts—adults were horrified by what they called the “juxtaposition of pure young lips and Hell.”

Religious swearing was taken more seriously than sexual or scatological profanity during much of the Victorian period. “Bloody” was considered a terrible oath (possibly derived from “by our Lady” or “God’s blood”), but “damn” was worse because it directly invoked the mechanics of divine judgment.

People genuinely believed that casual use of these words could invite evil influence or divine punishment. The supernatural was real and immediate. Words had power. Speaking of the devil might summon him. Invoking damnation might bring it about.

By the early 1900s, attitudes were beginning to shift. As faith became more personal and less literal, as urbanization and education spread, the terror of accidentally damning one’s soul through casual speech began to fade. The words gradually lost their shock value.

By the mid-20th century, “damn” had become mild enough to appear in mainstream films. In 1939, Clark Gable’s line “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn” in Gone with the Wind was shocking—but it made it into the film. The Production Code levied a fine, but the word was spoken.

Today, these words are barely considered profanity. They appear regularly in PG-rated content. Children use them. Nobody faints. Nobody’s soul is endangered.

The words that couldn’t be printed are now printed everywhere. The unutterable has become utterable. And somehow, the devil has not appeared.

—

Unpopular Conspiracies of the 1890-1910 Era

1. The Hollow Earth Theory (Symmes’ Hole)

While John Cleves Symmes originally promoted this in 1818, it lingered into the 1890s-1900s through followers and fiction. The theory claimed Earth was hollow with openings at the poles leading to inhabitable inner spheres. By the 1890s-1910 period, it had evolved into fringe science fiction but still had believers pushing for polar expeditions to “prove” the theory. The 1900 novel “Nequa, or The Problem of the Ages” still referenced Symmes’ theory as fact.

2. Ectoplasm Fraud and Spirit Materialization

While spiritualism was somewhat popular, the specific conspiracy was that mediums were being suppressed by establishment scientists who didn’t want people to know about the spirit world. Believers thought that:

– Scientists were deliberately debunking real phenomena to maintain materialist control

– The “ectoplasm” (which was actually cheesecloth, gauze, flour mixtures, and regurgitated fabric) was genuine spirit matter

– Photographs of “materialized spirits” were real, not dolls and papier-mâché masks

– The exposure of fraudulent mediums was itself a conspiracy to hide the truth

By the 1890s-1910s, this had become an elaborate back-and-forth with believers claiming exposés were cover-ups.

3. Phrenology and Criminal Skulls

While phrenology was somewhat known, the specific conspiracy theory was that:

– Certain skull shapes predetermined criminal behavior

– Society could identify “criminal types” before they committed crimes based on head measurements

– The government/police were suppressing this “science” that could prevent all crime

– “Thick skulls” indicated “mental languor” and criminal tendencies in non-white races

– Women’s skull shapes proved they were intellectually inferior

By the 1900s, this was still being used in prisons with detailed admission records measuring inmates’ foreheads, ears, and facial features for “phrenological research.”

4. The Theos

Ophical Hidden Masters Conspiracy

H.P. Blavatsky’s Theosophical Society (founded 1875) promoted the belief that:

– “Ascended Masters” from lost civilizations (Atlantis, Lemuria) existed in hidden locations (Tibet, the Himalayas)

– These masters possessed secret ancient knowledge

– They communicated psychically with select humans

– Modern science and religion were covering up evidence of these advanced ancient “root races”

– Elongated skulls found in Peru were evidence of these superior beings, not cultural head-binding practices

This influenced later archaeology conspiracy theories and was actively promoted in the 1890s-1900s.

5. The Jack the Ripper Royal Conspiracy

Less popular theories about Jack the Ripper’s identity included:

– He was protected by the royal family

– The murders were Masonic ritual killings

– The police deliberately botched the investigation

– Multiple copycat killers were being covered up as one person

– The killer was a prominent physician conducting experiments

These were fringe theories even then, not accepted by mainstream investigators.

6. The Protocols of the Elders of Zion (late 1800s origin)

Though published in Russia in the early 1900s, this fraudulent document claimed:

– Jews were conspiring for world domination

– They controlled world economies and governments

– International banking was a Jewish conspiracy

– The press was controlled by Jewish interests

This was proven a forgery by 1921 but originated in the late 1890s and influenced early 1900s anti-Semitism.

7. Fluorescent “N-Rays” Discovery Fraud

French physicist René Blondlot claimed in 1903 to have discovered “N-rays” – a new form of radiation. A conspiracy developed that:

– Establishment scientists were suppressing this discovery

– Only certain “sensitive” people could detect N-rays

– German and British scientists were denying N-rays existed due to national rivalry

This was thoroughly debunked by 1904 when American physicist Robert Wood proved Blondlot was experiencing observer bias, but believers maintained it was a conspiracy.

8. The Anti-Vaccination Conspiracy

While smallpox vaccination existed, a conspiracy theory emerged that:

– Vaccination was a government plot to control/poison the population

– Vaccines contained dangerous “animal matter” that would turn people bestial

– Compulsory vaccination laws were tyrannical overreach

– Doctors were in league with pharmaceutical companies to make money from unnecessary vaccines

– “Vaccine injuries” were being covered up

Anti-vaccination leagues formed in the 1880s-1900s promoting these theories.

9. The Airship Mystery (1896-1897)

Mysterious “airship” sightings across America led to theories that:

– A secret inventor had created advanced flying machines

– The government was testing secret aircraft

– The sightings were hoaxes by newspapers to sell papers

– Foreign powers (particularly Germany or Japan) were spying on America

– The airships were supernatural/demonic in origin

Thousands reported seeing mysterious lights and cigar-shaped craft before powered flight was achieved.

10. The Titanic/Olympic Insurance Swap Theory

After the Titanic sank in 1912, a theory emerged that:

– White Star Line deliberately switched the Titanic with its damaged sister ship Olympic

– The sinking was insurance fraud

– J.P. Morgan and other wealthy men who cancelled their trips knew in advance

– The iceberg collision was deliberate

This conspiracy theory has roots in pre-disaster insurance concerns from 1910-1911.

These conspiracies were less mainstream than the moral panics about bicycles, ice cream sodas, and ragtime music. They appealed to smaller, more specialized groups – occultists, anti-establishment scientists, racial theorists, and fringe believers rather than general public hysteria.

—

The Pattern

Between 1890 and 1910—a span of just twenty years—Americans and Europeans identified Satan’s hand in:

1. A source of power that lit cities

2. Women exercising their bodies and gaining mobility

3. A device that captured images

4. A dessert

5. A communication tool

6. A mode of transportation

7. Cheap popular literature

8. A moral panic about sex trafficking that led to racist prosecution

9. A musical genre created by Black Americans

10. Dancing

11. Traveling underground

12. Women making a certain sound with their mouths

13. Saying certain words out loud

Each panic followed a similar pattern:

– The new thing arrives

– Religious leaders declare it evil

– Medical professionals invent diseases associated with it OR Law enforcement invents criminal conspiracies around it

– Lawmakers pass restrictions or bans

– The public panics

– The thing becomes commonplace

– Everyone forgets they were ever afraid of it

– The panic moves to the next new thing

We have electricity in every building. Women ride bicycles wearing whatever they want. Everyone carries a camera. Ice cream is served on Sundays. Telephones are ubiquitous. There are nearly 300 million cars in America. Nobody criminalizes pulp fiction anymore. The Mann Act was weaponized against interracial relationships for decades. Ragtime became the foundation of American music. People still dance the waltz at weddings.

None of these things destroyed society. None of them were the work of Satan. Each of them was simply a new technology, social change, or cultural expression that made people uncomfortable—particularly when it gave freedom, mobility, or pleasure to women, young people, or racial minorities.

This is only the first twenty years.

—

“You’ll Go to Hell If You…” — The Complete List (1890-1910)

Based on documented moral panics, religious sermons, medical warnings, legislative records, and cultural superstitions from 1890 to 1910, here is what Americans were told would damn their souls, destroy society, or deliver them to Satan:

Technology & Infrastructure

You’ll go to hell if you…

– Use electricity in your home (it’s the “Unrestrained Demon”)

– Allow telephone lines near your property (they’re instruments of the Devil)

– Touch a telephone (you might get shocked, and it attracts evil spirits)

– Ride in an automobile (a “Devil Wagon” carrying souls to hell at thirty miles per hour)

– Take a photograph without permission (you’re a “Kodak fiend”)

– Have your photograph taken (the camera might steal your soul)

– Travel underground on the subway (you’re getting closer to the devil; it’s “the infernal hole”)

– Build subways through burial grounds (you’re disturbing the dead in the realm of Lucifer)

Women’s Bodies & Behavior

You’ll go to hell if you…

– Are a woman who rides a bicycle (you’ll get “bicycle face,” uterine displacement, become sterile, or turn into a prostitute)

– Are a woman who wears bloomers or pants while cycling (you’re blurring God-given gender boundaries)

– Are a woman who cycles unchaperoned (slippery slope to sex work)

– Are a woman who whistles (the heart of the Blessed Virgin bleeds; you’re summoning Satan; you’ll come to no good end)

– Are a woman who dances the waltz (you’ll faint from the “successions of agreeable emotions”)

– Are an unmarried woman who waltzes in public or private (it’s “too loose a character”)

– Are a woman who goes to a dance hall (the “ante-room to hell itself”)

Food & Drink

You’ll go to hell if you…

– Order an ice cream soda on Sunday (you’re breaking the Sabbath)

– Go to an ice cream parlor (especially one owned by foreigners—it’s a “spider’s web” for white slavery)

– Visit an ice cream parlor without a chaperone (you’ll be drugged and forced into prostitution)

– Drink ice cream sodas at all (they’re “training wheels for alcoholism”)

Entertainment & Culture

You’ll go to hell if you…

– Read penny dreadfuls or dime novels (they’re “printed poison” that will turn you into a criminal)

– Let your children read pulp fiction (they’ll rob their employers and become highwaymen)

– Listen to ragtime music (you’re falling prey to “the collective soul of the negro”)

– Perform ragtime music (it’s “the Ragtime Evil” and “whorehouse music”)

– Dance to ragtime (you’re engaging in “interracial mating games” and “devilish rites”)

– Play ragtime in your home (if you’re Christian, ragtime should “find no resting place”)

– Dance the waltz (you’re engaging in “voluptuous intertwining of limbs”)

– Dance the turkey trot, bunny hug, or grizzly bear (“animal dances” are immoral)

– Go to the theater and whistle (you’ll ruin the show and anger the sailors/stagehands)

Social & Moral Behavior

You’ll go to hell if you…

– Are involved in interracial relationships (you’ll be prosecuted under the Mann Act)

– Transport a woman across state lines for “immoral purposes” (including consensual relationships)

– Work as a prostitute (even though you may have chosen it willingly, you’re in “white slavery”)

– Own or work at a brothel in a red-light district (where ragtime was born)

– Allow your daughter to go to the city unchaperoned (she’ll fall into white slavery)

– Take public transportation alone as a woman (you’re at risk of being drugged and trafficked)

– Visit restaurants or dance halls as a woman (they’re recruitment centers for sex traffickers)

Language & Speech

You’ll go to hell if you…

– Say the word “damn” (you’re invoking eternal damnation casually)

– Say the word “devil” (you might summon him)

– Use the word “hell” in conversation (especially as a child with “pure young lips”)

– Say “bloody” (it’s a terrible oath derived from “God’s blood”)

– Let children sing songs with references to hell or the devil (horrifying juxtaposition)

– Whistle at night (you’re summoning demons; only demons whistle at night)

– Whistle in the evening (you make the angels weep)

– Whistle for forty days after whistling once (your mouth cannot be purified)

Race & Ethnicity

You’ll go to hell if you…

– Are Black and create new musical forms (ragtime is “symbolic of primitive morality”)

– Are Black and have relationships with white women (you’ll be prosecuted and imprisoned)

– Are white and marry or have relationships with Black people (multiple states tried to ban this)

– Are an immigrant and own an ice cream parlor (you’re running a white slavery recruitment center)

– Are Russian, Jewish, or Eastern European (you’re part of the white slavery syndicate)

– Embrace Black cultural influence (you’re contributing to “moral decay”)

Class & Literature

You’ll go to hell if you…

– Are working-class and read exciting stories (you’ll be dissatisfied with your station in life)

– Want adventure beyond your “narrow, monotonous” working-class existence (you’re aspiring above your class)

– Read stories with supernatural elements (Varney the Vampire, Sweeney Todd)

– Read detective stories or mysteries (they glamorize crime)

– Let boys read Buffalo Bill or Deadwood Dick stories (they’ll become criminals)

Transportation Specifics

You’ll go to hell if you…

– Drive an automobile on Sunday (you should be in church, not “Sunday motoring”)

– Drive an automobile at all (it’s a “despicable symbol of arrogance and power”)

– Drive faster than 12 mph in cities or 15 mph in the country (in Connecticut)

– Drive an automobile if you’re rich (it’s a “high-priced toy for the rich”)

– Drive where horses can see you (you’re terrifying innocent animals)

– Blow your automobile horn to make people jump (you’re an “auto fiend”)

Miscellaneous Victorian Superstitions

You’ll go to hell if you…

– Collect water from springs on the half-hour (it will be poisoned)

– Don’t throw rice at a wedding (the couple won’t be fertile)

– Don’t ring church bells as a couple enters (evil spirits won’t be warded away)

– Don’t stop the clock when someone dies (disturbing the soul’s departure)

– Don’t cover mirrors after a death (the spirit will get trapped)

– Don’t open windows when someone dies (the soul can’t escape)

– Walk under a ladder (inviting bad luck or demonic influence)

– Spill salt and don’t throw it over your left shoulder (you won’t blind the devil waiting to tempt you)

– See an owl near your house (death is imminent)

– Hear an owl hooting (someone in the house will die)

– Don’t hide a child’s shoe under the floorboards (you won’t have good luck)

—

The Pattern of Moral Panic

Looking at this comprehensive list, several patterns emerge:

1. New Technology = Devil’s Work

Almost every technological advancement was initially declared satanic: electricity, telephones, cameras, automobiles, subways. The pattern was consistent—if it was new and people didn’t understand it, it came from hell.

2. Women’s Freedom = Moral Decay

Women riding bicycles, wearing pants, whistling, dancing, going places unchaperoned, or expressing themselves physically were all signs of societal collapse. The real fear was female autonomy and mobility.

3. Black Cultural Influence = Primitive Evil

Ragtime music, dance, and any form of Black cultural expression was described in explicitly racist terms as primitive, morally corrupt, and demonic. The panic was about white cultural purity and racial hierarchy.

4. Working-Class Entertainment = Criminal Training

Cheap literature, dance halls, ice cream parlors, and any entertainment accessible to working people was suspicious. The upper classes feared that working people with imagination or aspiration would challenge the social order.

5. Privacy Loss = Moral Threat

Cameras, telephones, and public transportation all represented losses of traditional privacy and social control. The panic was about surveillance, accountability, and the inability to control information.

6. Interracial Contact = Existential Danger

The white slavery panic and Mann Act were explicitly about preventing racial mixing and maintaining segregation. The moral panic was weaponized against Black men, immigrants, and anyone who crossed racial boundaries.

7. Words Have Power = Literal Damnation

The Victorian belief that saying “damn” or “devil” could literally summon evil or cause damnation reflects how seriously supernatural threats were taken. Language wasn’t just offensive—it was dangerous.

8. Women’s Bodies = Public Property

From “bicycle face” to whistling to dancing, extraordinary attention was paid to controlling women’s bodies, movements, sounds, and physical expressions. The panic was always about loss of patriarchal control.

None of these things actually led to hell. None of them destroyed society. Many of them—women’s freedom, technological progress, cultural exchange, class mobility—actually improved society dramatically.

The panics were never really about the things themselves. They were about power, control, fear of change, and the anxiety that comes with social transformation.

Every generation finds its own devils. Every generation eventually realizes they were fighting phantoms.

This is only the first twenty years.

—

Sources & Notes

Electricity:

– “The Unrestrained Demon” political cartoon (1889)

– Harper’s Weekly, December 14, 1889

– Reports on John Feeks’ death, Manhattan, October 11, 1889

– Swedish telephone opposition documented in Ericsson historical archives

Women on Bicycles:

– Medical journal reports on “Bicycle Face” and related conditions (1890s)

– Raab, Alon. Research on bicycling opposition in the Ottoman Empire

– McGill University Office for Science and Society: “The Moral and Medical Panic Over Bicycles”

– Victorian-era medical warnings about cycling and female sexuality

Kodak Cameras:

– The Hawaiian Gazette, “The Kodak Fiend” (1890)

– Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis, “The Right to Privacy,” Harvard Law Review (1890)

– New York Times reports on Theodore Roosevelt and photographers

– British “Vigilance Association” reports from 1890s newspapers

Ice Cream Sodas:

– Sunday ban legislation in Evanston, IL; Massachusetts; Huron, SD

– Women’s Christian Temperance Union campaign materials

– National Geographic: “How ice cream became a Prohibition-era craze”

– American Historical Association: “Thanks, Prohibition! How the Eighteenth Amendment Fueled America’s Taste for Ice Cream”

– Mann Act documentation on ice cream parlors as “white slavery” recruitment sites

Telephones:

– Ericsson historical archives: “The telephone is the instrument of the devil”

– Swedish religious opposition documentation (early 1900s)

Automobiles:

– Chicago Tribune: “Is Automobile Mania a Form of Insanity?” (1902)

– The Motor journal (1902)

– Georgia Court of Appeals ruling on automobiles as “ferocious animals” (1906)

– Prince Edward Island automobile ban legislation (1908-1913)

– Vermont “red flag law” documentation

– Michael L. Berger: The Devil Wagon in God’s Country: The Automobile and Social Change in Rural America, 1893-1929

– Princeton Alumni Weekly: “Invasion of the devil wagon”

Penny Dreadfuls and Dime Novels:

– Springhall, John. “Penny Dreadful Panic (II): Their Scapegoating for Late-Victorian Juvenile Crime”

– The Speaker (1895), Dundee Courier (1896)

– Mimi Matthews: “Penny Dreadfuls, Juvenile Crime, and Late-Victorian Moral Panic”

– Emily Coombes murder case (1895)

– Jesse Pomeroy trial documentation

White Slavery:

– Mann Act (White Slave Traffic Act of June 25, 1910)

– George Kibbe Turner, McClure’s Magazine (1907)

– Edwin W. Sims statements on white slavery syndicate

– Fighting the Traffic in Young Girls: Or, War on the White Slave Trade

– Jack Johnson conviction and 2018 posthumous pardon

– PBS: “Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson”

– Multiple academic sources on Mann Act prosecution history

Ragtime:

– Edward Berlin: Ragtime (research on ragtime panic)

– Letters to The Musical Courier

– Canon Newboldt sermons and New York Times defense (1913)

– 1914 editorial quoted in multiple sources

– Leonard, Neil. Research on religious opposition to ragtime

– Contemporary newspaper coverage of ragtime moral panic

Dance Halls and Waltz:

– Knowles, Mark. The Wicked Waltz and Other Scandalous Dances: Outrage at Couple Dancing in the 19th and Early 20th Centuries (2008)

– McKee, Eric. Decorum of the Minuet, Delirium of the Waltz (2012)

– Mme Celnart, The Gentleman and Lady’s Book of Politeness (1833)

– Donald Walker, Exercises for Ladies (1836)

– The Times of London coverage (1816)

– Jane Addams writings on dance halls

– Waltzing Through Europe: Attitudes towards Couple Dances (Bakka, et al., 2020)

Boston Subway:

– Most, Doug. The Race Underground: Boston, New York, and the Incredible Rivalry That Built America’s First Subway

– Mass Moments: “Nation’s First Subway Opens in Boston”

– PBS American Experience: “The Race Underground” (2017)

– Boston historian Charles Bahne on underground as “realm of Lucifer”

– Historian Stephen Puleo on resistance to subway

– Boston Post: “Hideous Germs Lurk in Underground Air”

– Park Street Church pastor sermons on “infernal hole” (1895-1897)

– Central Burying Ground relocation documentation (1895)

– Gas explosion documentation (March 4, 1897)

– New York Sun coverage of subway opening (September 1, 1897)

Women Whistling:

– Notes and Queries correspondence (1879, fifth series, xii, 92)

– Popular Science Monthly, “Whistling” (June 1883)

– Various cultural documentation of whistling superstitions

– Victorian-era folklore collections

– Fern, Melora. Whistling Women and Crowing Hens (2024 novel set in 1924)

Victorian Blasphemy and Swearing:

– Mohr, Melissa. Holy Shit: A Brief History of Swearing (2013)

– Victorian Literature examples (Wuthering Heights, Anthony Trollope novels)

– English Language & Usage Stack Exchange discussions on Victorian profanity

– Victorian social conduct manuals and etiquette books

– C.S. Lewis writings on Victorian attitudes toward damnation

—

Coming Next: 1910-1930, featuring jazz music, comic books, flappers, movies, radio, and whatever else Satan was supposedly up to while we weren’t looking.

—

This is part of an ongoing documentary series examining moral panics throughout American history. Each installment covers a specific time period and the things people blamed on the devil, demons, or general moral corruption—before those things became completely normal parts of everyday life.

Leave a reply to william sinclair manson (Billy.) Cancel reply